Are You Ready For The Country?

Shannon McNally Does Right by Waylon Jennings in The Waylon Sessions

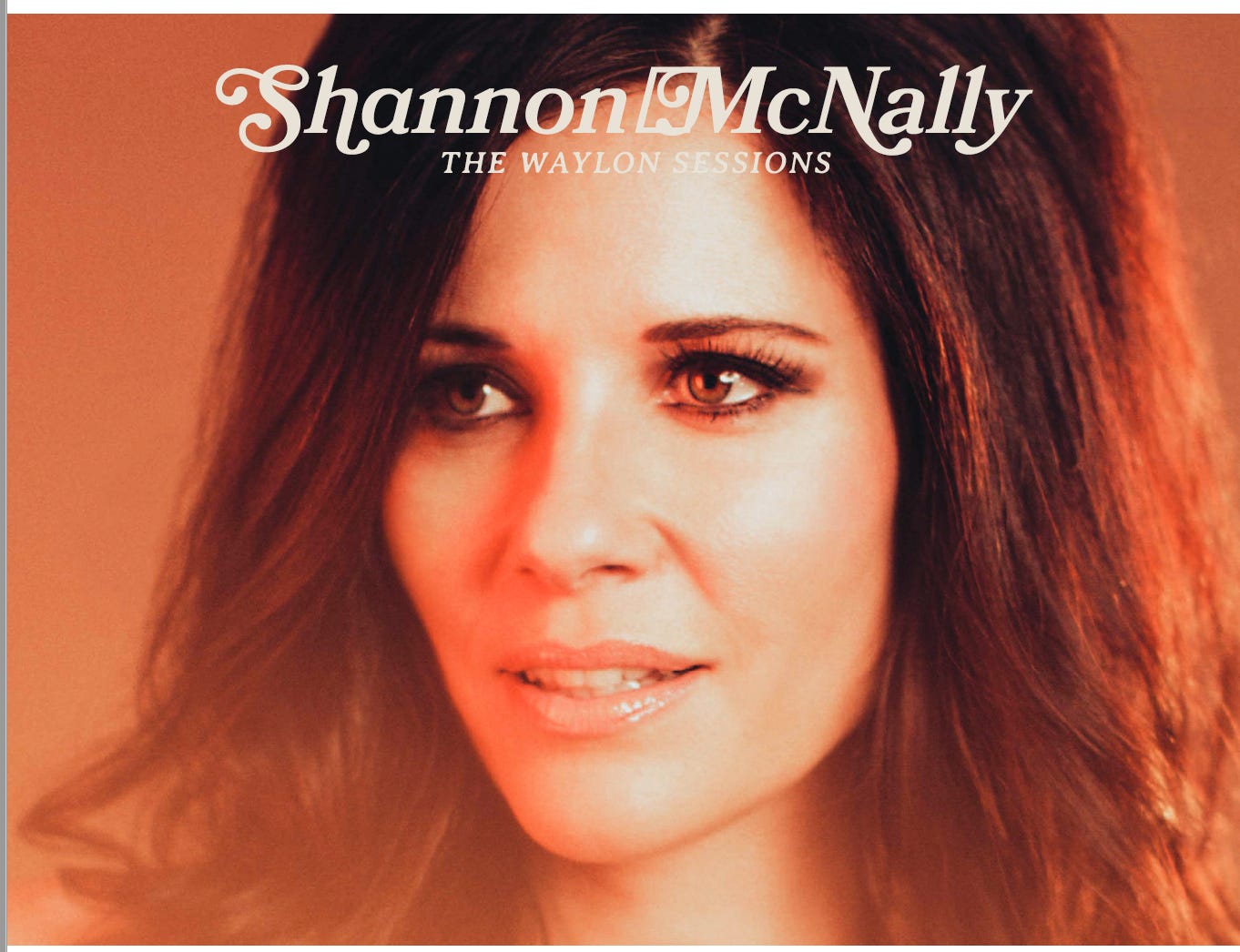

Shannon McNally: The Waylon Sessions (Compass Records)

Shannon McNally may sometimes be a singer-songwriter, but her true calling is as a songwriter's singer. Over her now 20 year career, she has been an excellent judge of songs that suit her voice, her style, her attitude, at any given time. Her excellent 2017 album, Black Irish features songwriters as diverse as Stevie Wonder ("I Ain't Gonna Stand for It"), J.J. Cale ("Low Rider"), and a version of Robbie Robertson's "It Makes No Difference," in which she matches the heartbroke eloquence of Rick Danko's vocal on the original by The Band.

She's even done albums dedicated to one songwriter: Small Town Talk was a tribute to the songs of the underappreciated New Orleans songwriter Bobby Charles. So what's the big deal about The Waylon Sessions, McNally's new album of songs made famous by Waylon Jennings?

Testosterone, for one thing. Even by Texas standards, Waylon Jennings evokes the Manly Man, the rugged range rider, as one of his songs g…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Critical Conditions by Wayne Robins to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.