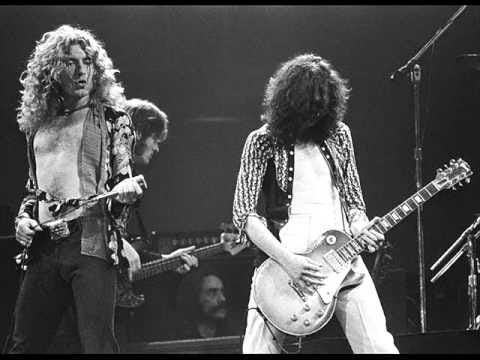

If you look at the avatar for this Substack, it's a soon-to-be-replaced thumbnail of the back page, then the Arts cover page, of New York's weekly Village Voice for Feb. 3, 1975. Ten days earlier, the Voice, then arguably the country's most influential weekly newspaper, sent me to Chicago to see and have a few words with Led Zeppelin. The legendary-in-my-own mind headline was created by me and my editor, Robert Christgau. Once we painstakingly line-edited every word and punctuation mark, as was Christgau's approach, we found the page designers had given us a tiny two-line/eight character box for the headline. We free associated until we came up with the words and the properly zany spelling Led Zep/Zaps Kidz. I'd been writing regularly for Christgau at the Voice since he became music editor and my day job at CBS Records ended with corporate cutbacks in spring/early summer 1974. I read it now and I wonder, who were we writing for? (I transcribed this version from the newsprint, so any t…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Critical Conditions by Wayne Robins to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.