I remember the day I got turned on to Pharoah Sanders. Sophomore year at my old school, I am in my dorm room on the first floor and hear these sounds coming from the third floor and across the hall. I feel summoned by these sounds, to climb the stairs, to follow the notes, to enter the room from which the music emanated. It was the roost of a classmate, Ken Vermes, who all these years later is still a saxophonist in San Francisco.

That's the way we found new music in those days. We followed the sound. One generation passed mixtapes to turn each other on; it was the same impulse: You've got to hear this, you're going to love it. I feel sad for my college students with their solitary ear buds, who do not have that opportunity: the communal music, the open doors, the way we made friends and created bonds to each other, and to the music. We loved to turn each other on to music. It was a gift.

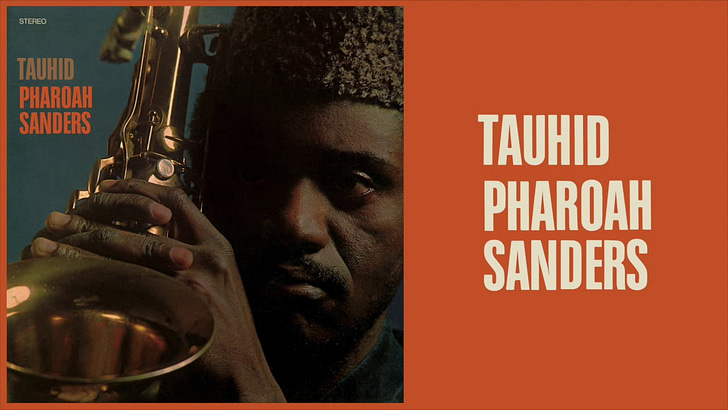

The music was the album Tauhid by Pharoah Sanders. One song, the 17 minute "Upper Egypt, Lower Egyp…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Critical Conditions by Wayne Robins to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.