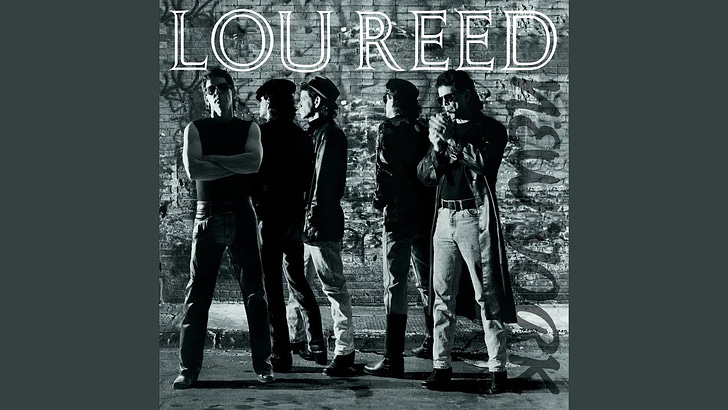

In early winter 1989, I met with Lou Reed for a nearly two hour interview at his office on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Months earlier, we were in an elevator at his label office and he was friendly as can be, volunteered that he “liked my stuff.” I said, “how about we do an interview for your next project?” He said that would be cool. But when we sat down, he was in a different mood. He made sure I had a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad day. Defensive, combative, uncooperative, and not always truthful. His album New York would be released in January 1989. I liked it a lot, these noir-ish songs taken from a decade of bad news from the city’s tabloid newspapers, including mine, New York Newsday.

I use this story to teach you can still get a good story out of a bad interview. You call people who know him, who can explain him. I found a former poetry teacher, a filmmaker, a rock musician, and a famous magician, among others, to frame the picture for the reader. Still, I cut some of …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Critical Conditions by Wayne Robins to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.