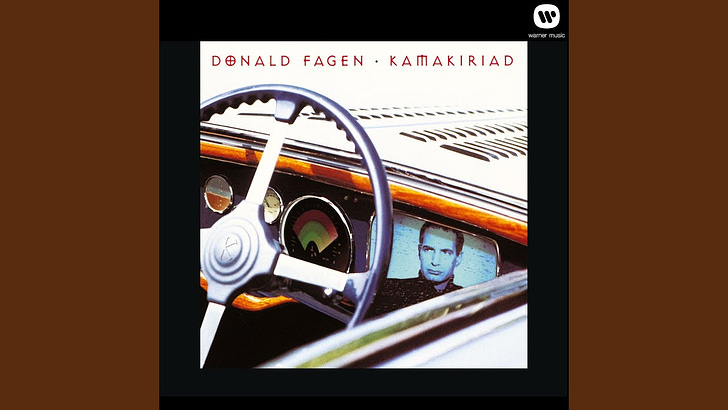

Donald Fagen's second solo album, Kamakiriad in 1993, more than a decade following the lauded The Nightfly in 1982) is a concept album. No, really, it really is a concept album, spelled out in the liner notes/lyric sheet to the Reprise Records CD. There are eight "related" songs, and Fagen tells us what they are about:

"The literal action takes place a few years in the future, near the millennium. In the first song 'Trans-Island Skyway,' the narrator tells us he is about to embark on a journey in his new dream car, a custom-tooled Kamakiri. It's built for a new century, steam driven, with a self-contained vegetable garden and a radio link with the Tripstar routing satellite. The next six songs describe his adventures on the way. In the last song, 'Teahouse on the Tracks,' the narrator lands in dismal Flytown, where he must decide whether to bail out or to rally and continue moving into the unknown."

As visions of the future go, it seems odd: the millennium of which he writes is the 21st…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Critical Conditions by Wayne Robins to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.