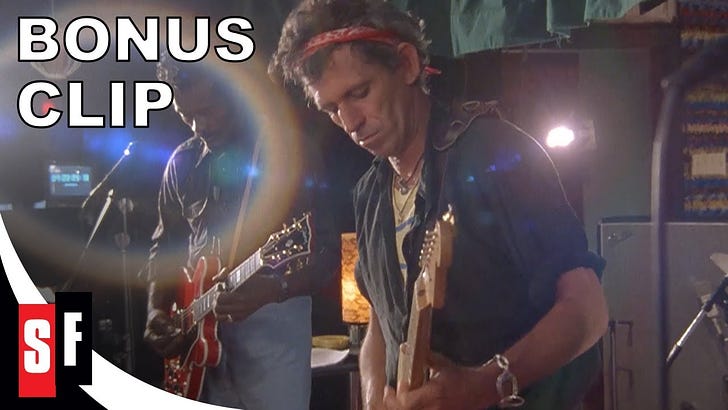

Playing Air Guitar With Keith Richards

Bourbon Included. But Should I Have Toked with Bob Marley?

An update from the real world. I am about to become a grandfather for the first time, courtesy of Liz Robins, Esq., and her husband, Dr. Aaron Potash. We know it’s going to be a boy. My requests to name him Mookie Potash-Robins, or Robins-Potash, after both Mookie Wilson and Mookie Betts, appear to have been declined. Dr. Potash is a pediatrician at the hospital at which Liz is about to give birth in the next 24 hours. Smart daughter, that Liz. (And smart son-in-law, too!) So we’re not nervous-nervous, just fu-fu-fu-fu-freaking out nervous! So I’m going to be distracted for a few days, will post photos when permitted and next essay soonest. Here is the pinned essay from Critical Conditions, an old favorite to tide you over. Thanks for your good wishes, WR.

After I wrote about my sober epiphany in 2010, I heard privately from many people I respect and admire who struggle with the same malady. It is heartening that opening up about alcoholism helped others. That is the point of recovery,…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Critical Conditions by Wayne Robins to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.