Ramones 101

Teaching Punk to College Students in 2023

For those who don't know, my part-time day job is teaching at St. John's University is my native Queens, NY. I teach five courses over two semesters; two in the spring, three in the fall. Each semester there is a class related to music and arts criticism. For Writing About Music: Pop, Rock, Rap (ENG 1074) the semester that just ended, I devoted a section to punk rock, specifically, the Ramones.

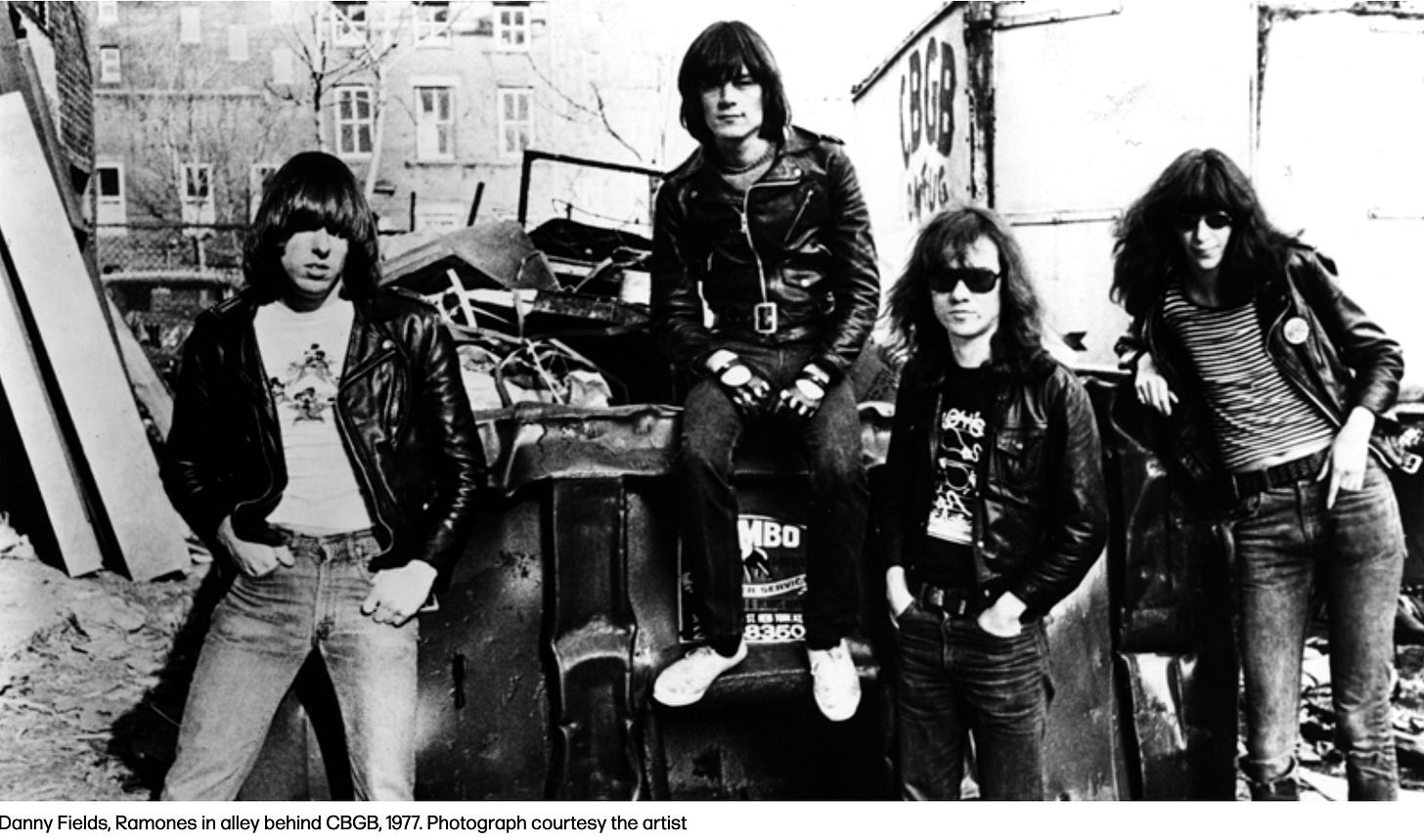

The Ramones remain the sun around which punk rock orbits. Who woulda thunk it? Streets in their native Forest Hills, Queens, and their adopted East Village, are named after these one-time pinheads. Movies are made about them, some in Spanish, because for some reason, they remain gods in Argentina, where the divine trinity is Maradona, Messi, and Joey Ramone. In 2016, the Queens Museum of Art held the most popular exhibit in its history: "Hey! Ho! Let's Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk," which opened April 10, through July 31, 2016. There may have been an extension before the exhibit moved to the Grammy Museum in Los Angeles that fall.

Here is my strategy for teaching the Ramones, using five or six 90 minute classes.

I walk into the classroom, and without saying anything, I turn on the audiovisual equipment built into the podium and play the song "Blitzkrieg Bop." For the students that like it, which is many of them, there is good news: Almost every other Ramones song sounds just like it. I play a selection of Ramones' originals, especially those early tunes with "Wanna" in the title: "I Don't Wanna Go Down to the Basement," "Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue," "I Wanna Be Your Boyfriend," and "I Don't Wanna Walk Around With You." I somberly read the lyrics to the latter song, as if it is heavy literary lifting, like something out of "Hamlet" or "King Lear." Because just about the entire lyric of the song is: "I don't wanna walk around with you," repeated three times, answered by, "so why you wanna walk around with me." The comedian and jazz pianist Steve Allen, a popular TV show host of the 1950s, used to do the same with Little Richard lyrics.

I give a brief cautionary tale about glue-sniffing, how it was the very bottom of the drug users food chain. It began as a youth culture thing in the mid-20th century, when building model airplanes was a thing. The glue that came with model airplane kits could give a kid a kind of dizzy psychedelic buzz. You could even die from it. I explained that as an amateur youth pharmacologist, willing to sacrifice my brain and body to just about anything that would get me out of my own miserable teenage head, not even I ever huffed glue. Even to the Ramones, glue sniffers were lowlifes.

Required reading: Donna Gaines' introduction to her book, Why the Ramones Matter, (2018, Univ. of Texas Press.) used by permission. (She wrote that she sniffed glue growing up in Rock-Rock-Rockaway Beach.) Dr. Gaines is an internationally acclaimed sociologist, a professor and mentor since 2013 at SUNY's Empire State College. She is not only a devout Ramones fan, she is also a hardcore head banger. Tall, raven haired and gorgeous, black leather jacket, tight jeans, and knee high boots, Dr. Gaines came to fame at the Village Voice in the 1980s and 1990s, for which she did field work with the no-future teenagers who hung out at a certain 7-11 in the New York region suburbs New Jersey. The Voice article or articles and resulting book were called Teenage Wasteland: Suburbia's Dead End Kids, (Pantheon, 1991) with as much acuity and less distance than Pete Townsend did in his Who song that made that phrase famous, "Won't Get Fooled Again."

Dr. Gaines preface to her Ramones book uses phrases deliberately evoking "the rooms" of recovery: "My name is Donna and I’m a sociologist. The Ramones have been a de facto higher power for over forty years. Even now, post-ascension, they’re still my psychic protectors. Their music buffers me, as a participant-observer, against a social world I study formally but never fully engage with...”

"They offered a subterranean view of post–World War II America I could work with; high theory, low culture. Before you realized it, you were abducted by the Ramones, sucked up into a cultural rebellion, a covert operation, a social movement. By the time you figured it out, the band had changed your life."

I play the song "Pinhead," which contains the Ramones most defining but at first obtuse slogan: "Gabby Gabby Hey." It is the tent under which all Ramones fans gather, are drawn to, as if in a trance.

To flesh out the meaning of "gabba gabby hey," I ask the rhetorical question: "What is the worst thing about the first day in a new high school, where you don't know anyone, and are really depressed about leaving your old friends behind?" Home room? No. Gym class? No. The way it happened to me, my anxiety all morning in September 1963 at Herricks High School on Long Island, first day of ninth grade, where I never completely adjusted even after four years, was about lunch. Who would I sit with in the cafeteria? Or at least, which group could I sit alone near, that might be the least threatening? I stood alone, paralyzed, holding my tray, unable to decide until almost the end of the period, when some spaces opened up and I could scarf down some food alone. What I was looking for, but didn't know, was that I belonged to a different tribe, yet to be born: I had the Ramones in my DNA, and my brain scanned every short wave band, every radio telescope for signs of life, but it wouldn't be until 14 years in the future, on the 1977 album Ramones Leave Home, that the message appeared:

"Gabba gabba we accept you one of us." A new flag, a new tribe, for those who didn't fit with the primary cliques, of jocks or greasers, the only cliques at Herricks and most suburban high schools at the time. In a few years, there would be stoners, but I would be long gone. Hardly anyone knew me in high school, but at the tenth Herricks reunion (class of 1967), everyone knew my name, everyone knew who I was. I was the guy in the newspaper with a readership of one million, writing about the music they all listened to. I got my PhD at CBGB.

It is here that I go into one of the digressions for which I am known in the academy, or at least among former students. Donna, as I have described her, was my braintrust and bodyguard for shows by Metallica, and by Megadeth at Nassau Coliseum. She knew the names of all the songs. Every once in a while, Donna left me alone in my loge seat, but I always knew where to find her: slammin' her body around in the middle of the mosh pit.

Both of us are former avid chasers of the intoxication of alcohol and other substances. Dr. Gaines once lived in an apartment complex in Mineola, Long Island, the county seat of Nassau County, where all the goverment buildings were, including county police headquarters. All fired up after a Metallica concert, we decided to stop in for a drink at the nearest open bar to her apartment. That bar across from police headquarters was, in the parlance of the saloon industry, a "cop's bar." Lucky us! The cops just getting off their shift took one look at Donna and the testosterone level in the joint went through the roof. And Donna, being already a few sheets to the wind, did not suffer gladly the barbed and sexist comments. She pushed back. Before the cops' attitude towards us turned from bemused hostility to something that might very quickly cause us to break out in handcuffs, I took one sip of my beer, put my arm through Donna's, whispered the secret bat code: "Hey, ho, let's go," and whisked her home with the speed of Usain Bolt.

It was one of those insanely memorable events in a drinker's life, so I promise you it happened. When I tried to reminisce about it with Dr. Gaines a few years ago, she said: "Really? Oh, those blackouts!" We went back to her place and sniffed some glue...no, we didn't really do that part. The rest is true.

Meanwhile, back in the classroom: I play some Ramones covers, the early 1960s pop songs they liked, including "Let's Dance" by Chris Montez, and sometimes, as suggested by Mets' TV anchor Gary Cohen, himself a Ramones fan, is which version of "Surfin' Bird" does one prefer? The "original" (itself a knockoff of the Rivingtons' "Papa-Ooh-Mow-Mow") by Minnesota's surfin' Trashmen, or the Ramones' version?

By now the students know they are in foreign territory: this isn't Green Day, or Blink-182, or the other "pop punk" they might have heard: this is the pure, uncut stuff. I also play the Ramones' "Rockaway Beach," play an apt song by the Beach Boys, and then swing to You Tube, where one can find, if one really wants to, Mike Love of the Beach Boys performing the Ramones' "Rockaway Beach." You see? For all the dark drama of the black leather jackets and torn jeans, for all the speed of bass player Dee Dee Ramones' "1-2-3-4," the Ramones were, essentially, an evolution of all-American surfing music.

At least that's the point I tried to make to Scott Muni, long time New York disc jockey, from the old WABC top 40 radio. Muni's power had grown when he switched to WNEW-FM, the most important rock radio station in New York in the 1970s and 1980s, I think, though there were occasional ratings declines during the disco era, which was probably happening then.

Muni and I tangled on a radio panel at C.W. Post College in Greenvale, Long Island. Late 1970s, I guess. I politely asked Mr. Muni why his radio station did not play local heroes, the Ramones, who were nothing if not New York's version of the Beach Boys, which WNEW-FM played all the time.

"Our listeners don't like their image," Scott Muni said.

To which I said, "Image? Scott, this is radio, people don't see any image, they hear the music."

To which Muni replied not a word. He went red in the face, came up to my face so I could smell his sulking whiskey breath, and he could smell my vodka breath. We breathed on each other. And that was that.

We spend another class on the New York bands who sounded not all like the Ramones or each other in the CBGB non-melting pot, one of the moments in time and space that Brian Eno once described as "scenius": the genius of artistic types collected in one scene, all doing their own thing but somehow cohering as a scene. I played Patti Smith Group's "Gloria," Talking Heads' "Psycho Killer," and Richard Hell and the Void-oids "Blank Generation." I wanted to play all of Television's guitar rock masterpiece, the ten-minute title song of their immortal 1977 debut album, Marquee Moon. But having been warned many years earlier that the attention span of most college students is no longer than six minutes (now it is shorter), I played instead the song "Venus" from that album, which features Tom Verlaine's genius/scenius line: "I fell into the arms, of the Venus de Milo."

Looking for my 2023 students who have time traveled to London 1977. Doctor Who is standing outside the Tardis

Okay class, who knows what's funny and trenchant and tragic about this line? Who knows what "the 'Venus de Milo'" is? No hands raised, which doesn't mean that they didn't know the ancient Greek sculpture, they might not have felt like raising their hands. I Googled the famous statue and put it on the screen: Venus, the goddess with no arms. "Get it, I fell into the arms of the Venus de Milo?"

They did not reply, "oh yes, we see." A tough crowd to work.

We went to England for a few classes, visited with the music of the Sex Pistols: "God Save the Queen," "Anarchy in the U.K.," and "Pretty Vacant." Told my Sid Vicious and Johnny Rotten anecdotes. Then, a class and a half on importance of The Clash, from "Janie Jones" to "Rock the Casbah."

It was now time for them to write a paper. On You Tube, there is a 29 minute video that plays like an entire Ramones concert: Dec. 31, 1977, New Year's Eve, the Ramones Live at the Rainbow in London. The idea was to time travel to that event, and write an essay about what it was like to experience this moment. Most students did good enough papers.

The best students, however, disappeared through that hole in the space/time continuum, and did not come back. And I’m an adjunct, without tenure! I went to the nearest British police calling box (which contains a space/time ship called a Tardis) and asked my associate, Doctor Who, to set the controls for that night and time in London. We found my students exiting the Rainbow chanting "gabba gabba hey, we accept you one of us," directed them to the Tardis, and delivered them safely back to the classroom on the third floor of Marillac Hall in April 2023. End of lesson.

It was great fun, actually, LkTIV. At least that section. I’m a New Balance man, myself. Better for the aging feet.

Excellent. I'm glad I'm not in your shoes. Are they Converse?