Part One: Talking to Talking Heads, Oct. 1977.

IT IS only three years since three friends from the Rhode Island School of Design moved to New York, bent on developing their careers as artists. David Byrne, Chris Frantz, Tina Weymouth and a fourth friend, Jerry Harrison, apparently accomplished last week what they set out to do.

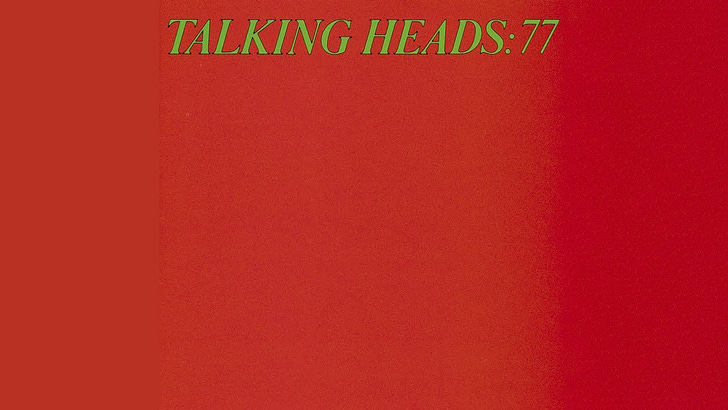

They had to give up art supplies and pick up musical instruments in order to do that. They call themselves Talking Heads, and the quartet's debut album, Talking Heads: 77 has just been released by Sire Records.

The album lives up to the expectations of the cult of devotees that have followed the band in its appearances at CBGB, the Bowery rock club, during the last two years. It is vital, quirky, sometimes obtuse, but always intelligent. Though some of the music mixes the traditions of white 1960s rock and soul music with a dollop of reggae, the result is the most original interpretation of that source material that has been created in years.

Though the music most …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Critical Conditions by Wayne Robins to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.