"The murderous attack on Ukrainians is also a kind of cultural and historical cannibalism."

--Sophie Pinkham, in an emailed interview with Lucy Jakub, New York Review of Books, March 12, 2022

There is something universal about the reaction to Russia's wanton destruction of Ukraine, its unprecedented scale, the promiscuous bombing of civilian buildings, including but not limited to maternity hospitals, houses of worship, and even Russian historical landmarks: The continuing lack of belief that this could really be happening. As Pinkham, an American author and memoirist who first lived in the Ukraine in 2008, points out, "for Putin to bomb the city that’s home to the eleventh-century St. Sophia Cathedral, one of the only remaining buildings from Kyivan Rus' [the medeival origin of Russia] . . . is like bombing the grave of his own ancestors. I guess he doesn’t care."

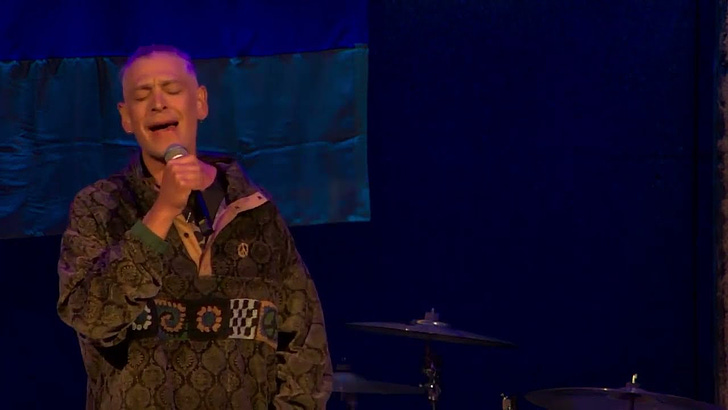

Matisyahu sings at New York’s City Winery benefit for Ukraine

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Critical Conditions by Wayne Robins to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.